Autoformalization and the Future of Math Research

Formal methods reveal which informal concepts we rely on most.

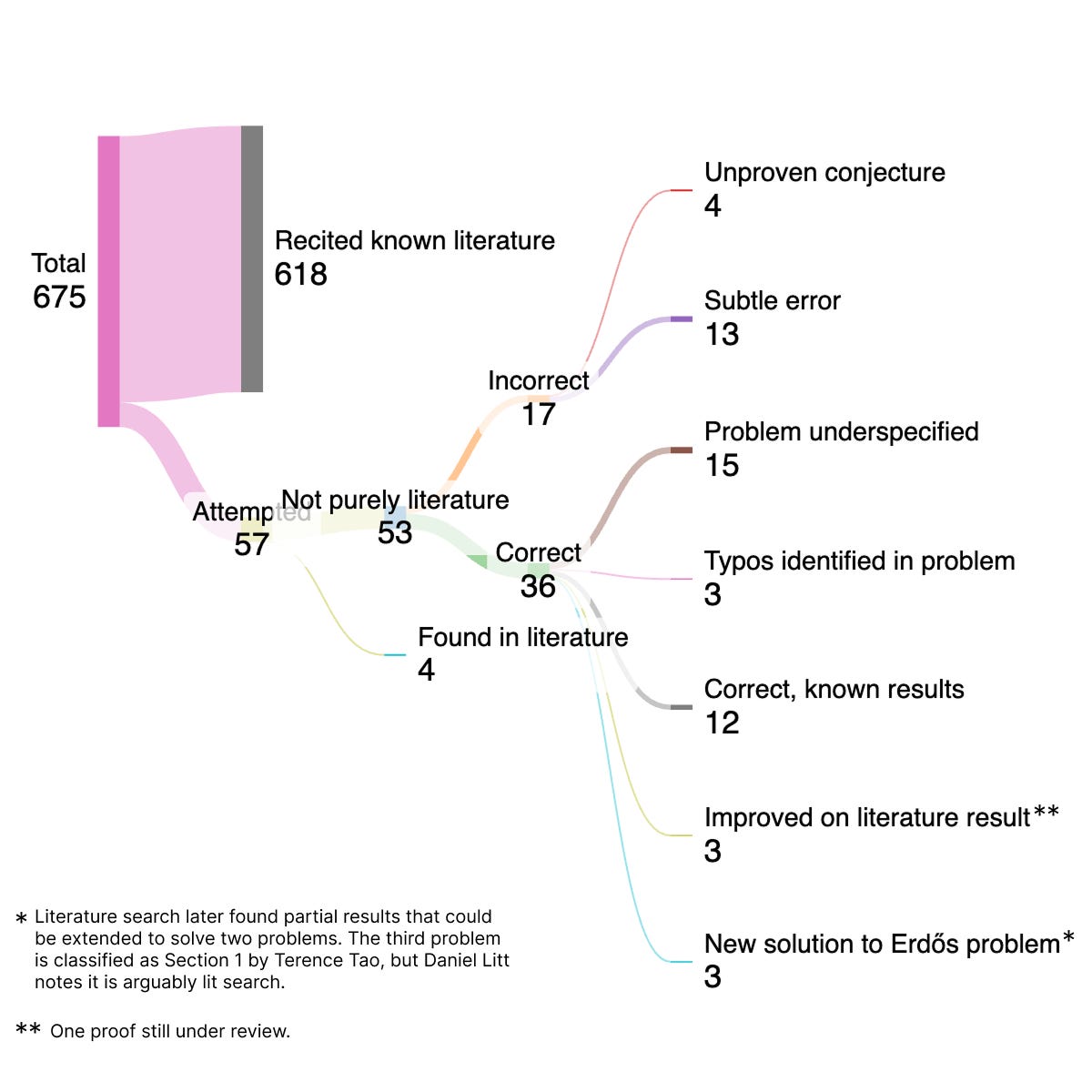

Last week, I gathered a group of bright undergraduate students to construct GPT-Erdos. We ran a uniform procedure across the open Erdős problems, evaluating GPT-5.2 Pro, Deep Research, and when possible, Aristotle by Harmonic. This produced 3 accepted solutions, 3 partial results, and 4 previously undocumented rediscoveries, all open-sourced.

What I found is that the value of autoformalization goes beyond the raw tech. (By “autoformalization,” I mean the tooling that takes a human-readable math proof and converts it into a machine-checkable format like Lean or Coq.) By formalizing our work, we expose underspecified concepts that implicitly guide research, like novelty, progress, and correctness.

The Most Common Failure is Underspecification

Early experiments made it clear that failure cases can be nuanced. For example, GPT 5.2 Pro produced an accepted solution for problem #397, but shortly thereafter Terence Tao used Deep Research to find a partial result that was closely related. The solution took a different path than GPT 5.2 Pro, but it could likely be extended to solve the same problem. Depending on who’s the judge, this could be described as a novel result, a rediscovery, or an extension of existing literature.

So I became interested in what the failure modes were when GPT 5.2 Pro fails to give a novel result, or when it might succeed. The methodology was simply pasting the exact LaTeX problem statement into GPT 5.2 Pro, and asking Deep Research to surface any previous solutions, resembling the process that #397 followed. No human intervention was allowed during generation. Each response was independently reviewed and classified according to predefined categories. Our open-source results are consistent with what others have found:

What stands out is that if you’re only looking at the non-trivial attempts beyond pure literature recitation, underspecification causes at least as many failures as outright errors.

Relatedly: Finding existing literature, expanding on it, and producing structurally new proofs are useful results, but I found that psychologically, people want there to be a clear “novel” result attributed to an LLM, with no historical literature or partial results. Disagreements over novelty aren’t purely epistemic. Novelty functions as a proxy for intellectual contribution, and it’s also a measure of which proving system is the most advanced. That creates pressure to draw clean delineations around what’s “actually novel.”

Informal Goals Guiding Formal Methods

Top mathematicians disagree on whether a result is novel. For example, in problem #652, Tao classifies the GPT 5.2 Pro response as novel, but the result heavily relies on Mathialagan’s bipartite theorem. One solution (#281) was interesting enough that Nat Sothanaphan wrote a great write-up on it and Tao wrote about the method on his blog.

Of course, in math almost everything in some way builds upon previous results. The question is whether there was a non-trivial insight, perspective, or approach applied to a problem. One extreme interpretation is that nothing is novel or that everything is. Neither reconciles with our intuitions around novelty.

Maybe the correct definition is something closer to the minimum complexity of expressing a proof, while being allowed to reference existing results with constant cost. In other words, if a proof is an existing theorem with new parameters, that’s pretty simple to express, but if a proof requires several new non-trivial theorems and there’s no way around expressing it that way, that’s more complex and probably novel.

Or another possible formalism might take inspiration from zero-knowledge research, where we show it’s possible to be convinced of the truth of a statement while not being able to reconstruct the underlying witness given polynomial time computation. In an analogous sense, we can define mathematical “knowledge” as the ability to reconstruct a proof using existing results in polynomial time. So retrieving an existing theorem and substituting new parameters wouldn’t count.

A formalism like that helps if we give the LLM the problem that we want to solve. But at some point the LLM needs to have some sense for which problems are the most “interesting” to solve, too. And that seems harder to formalize. Interestingness is sometimes a proxy for utility (does this help us solve other problems in math/physics?) but sometimes the utility is unclear.

The critique obviously extends beyond just math. The LLM has no way of knowing what business ideas are most interesting or novel, or which art pieces are the most meaningful. None of that is a part of the training process, and the post-training process is so heuristic that I wouldn’t bet all the properties we care about are emergent. So maybe these are important concepts to formalize. Applying formal methods has a way of revealing which informal concepts we rely on most.

Where’s the Space Heading?

I can’t find the tweet, but somewhere Daniel Litt says something along the lines of: “Even if LLM progress completely stalled, the existing technology will substantially impact the practice of mathematics.” I think that’s very true. Mathematicians spend their time verifying proofs by hand that can be checked by Aristotle; people spend time on “open” problems that are sometimes already solved in the literature; quickly getting up-to-speed on existing approaches to a problem can save significant time. Of course, I think the models are going to get way better at math. Though we might need new techniques.

Regardless, people keep asking me where this is going. What good is proving? Sometimes you hear answers like quant finance, but we don’t really formally prove things in quant finance. But we definitely develop models that you’d want to be provably correct.

For example, can we say with certainty that a particular C/C++ CUDA kernel has no memory safety violations? Can we say that a program handles all exceptions gracefully? Are there outputs that a statistical model provably cannot internally represent?

These are all well-studied questions prior to autoformalization, but no one wants to use a super sophisticated type system, so I see autoformalization as a way of applying formal methods at scale. In that same vein, we have so much slop code being produced by LLMs that no one’s checking that carefully. Provable guarantees become a lot more valuable when there’s no close supervision.

The other thing that I hope emerges from autoformalization research is some concept of “closeness” to completion. No such metric is widely accepted to my knowledge. I think Terence Tao has some old essay or video where he points out that experienced mathematicians make errors too, but the errors tend to “cancel out” since the intuition is sound. Conversely, a single error can throw a junior mathematician completely off course. In short, there’s a difference between a proof that’s trivially reparable vs. one that’s fatally flawed, but final formal verification is binary: either the proof verifies or it doesn’t. In an ideal world, that closeness function would be a differentiable surrogate so we can optimize it directly.

The concept of closeness to completion matters in a bunch of domains. For one, it serves as a search oracle when you’re trying to find the right solution for something. But second there’s a ton of domains where the binary “proves vs. doesn’t prove” would fail. The Einstein field equations were famously discovered via a variety of heuristics and metaphors, and they were only cleanly formalized by later physicists. In general, the process for discovering truth is heuristic, not formal. Coincidentally, that resembles the state-of-the-art in autoformalization today; the gold standard is GPT 5.2 Pro for finding the proof, then Aristotle by Harmonic for verifying it. Almost all of the AI-solved Erdos problems were derived this way to my knowledge.

There are lots of other cool domains to apply autoformalization and formal methods to, so I’m curious to hear other people’s ideas!